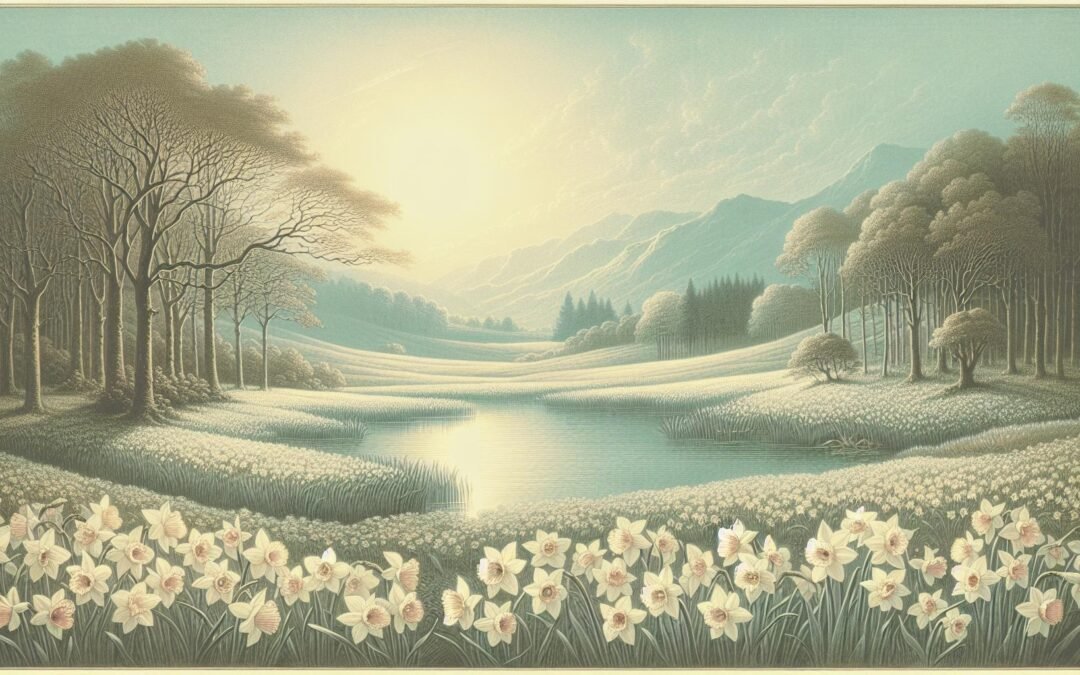

William Wordsworth’s “Daffodils” remains a touchstone of English lyric poetry, echoing through the centuries with the same exuberant spring as the flowers that inspired it. Born of solitude and observation, its music invokes the Lake District’s radiant evenings when golden heads swirl upon the wind-laced shores of Ullswater. Here, emotion and landscape converge—imagination becomes inseparable from the trembling dance of nature, inviting reflection on how memories gather their own bloom. In these lines, the Romantic passion for sensation and recollected tranquility finds its most vivid testament. This singular composition invites both aesthetic and philosophical exploration, much as other masterworks of Wordsworth and Coleridge do for scholars and lovers of poetry alike.

“Daffodils” and the Power of Memory

Early spring sunlight brightens the Cumbrian fells as it awakens the daffodils that gather by the rippling water. Wordsworth, having wandered “lonely as a cloud”, finds in these yellow ranks not a passive backdrop, but vibrant company. The poem unfolds in four measured stanzas, each carrying the lilting rhythm of iambic tetrameter and an ABABCC rhyme scheme. Every measure breathes with cyclical return, mirroring how childhood scenes repeat in later reverie. The daffodils, “continuous as the stars that shine and twinkle on the milky way,” inspire a vision where perception magnifies an earthly multitude into cosmic profusion, much as exemplary imagery in poetry transforms ordinary things into sources of astonishment.

Impression seeps into consciousness long after footsteps fade. Wordsworth crafts his recollection around the “inward eye,” a phrase that crystallizes his conviction: lived experience gains significance in tranquil meditation. The daffodils, once “dancing in the breeze,” return “when on my couch I lie in vacant or in pensive mood.” Memory becomes artifact and conduit, gathering joy for what was first glimpsed on a lakeside path. This transformation, more than mere reminiscence, enacts a poetic philosophy articulated in Wordsworth’s Preface to Lyrical Ballads and echoed through studies of metaphor in poetry. Daffodils’ luminous apparition emerges not only from the moment but also from the act of recollection that enriches the soul’s reserves.

The Aesthetic of Nature’s Community

In the opening stanza, singularity and communion entwine. The poet, adrift above the world in cloudlike seclusion, encounters “a crowd, a host, of golden daffodils.” They appear not as a static cluster, but “fluttering and dancing in the breeze,” scattered with grace beside the water’s edge and beneath budding trees. The daffodils’ joyful unity carries a vision of nature’s fellowship that counters the speaker’s initial estrangement. This vision makes nature’s communal energy palpable in a way that prefigures later studies into the diverse forms of poetic love, where individual longing is transformed in gathering and togetherness.

The daffodils, pictured as “tossing their heads in sprightly dance,” convey a movement that blurs the human and the more-than-human. Animate and radiant, they reflect not only mood but also a vibrant order within nature itself. Through this choreography, Wordsworth imbues the landscape with consciousness and expression—his personification foregrounds how poetic perception heightens kinship with the outer world. Their collective form recalls poetic ensembles examined in the context of history’s most influential poems, revealing how the Romantic imagination resists alienation by recognizing shared delight in the spectacle of the natural.

Language, Symbolism, and Sensory Music

Imagery abounds with sight and motion. Lexical choices revolve around “golden,” “fluttering,” “glee,” and “jocund company.” Wordsworth’s daffodils are not static tokens, but brilliant presences whose animation conveys a mingling of earth and spirit. The poet, guided by the restorative force of landscape, presents a scene charged with aliveness. “Ten thousand saw I at a glance”—the number is not meant to be counted, but to hint at the boundless effect of awe upon the perceiving mind. Emphasis on multitude, as in lines “[continuity] as the stars that shine and twinkle on the milky way,” elevates the scene above the earthly.

Repetition and echo infuse the poem’s form. Rhyme patterns, the interplay of “breeze” and “trees,” “cloud” and “crowd,” mirror nature’s recurrent motions. This musicality draws readers into a mood that is both tranquil and exultant. Similes and metaphors construct a luminant bridge between perception and mystery, building on poetic traditions explored in studies of Keats’s ode and Romantic verse. The daffodils’ brightness is never glaze alone; it hints at the promise that nature “fills the heart with pleasure.” The effect recalls Romantic convictions regarding art’s potential to heal and uplift. For those seeking a cross-cultural parallel, Poetry Foundation offers a wealth of background on Wordsworthian style and its enduring legacy.

Memory, Mood, and the Evolving Self

The final stanza draws focus toward interiority: “For oft, when on my couch I lie in vacant or in pensive mood, they flash upon that inward eye which is the bliss of solitude.” Wordsworth’s treatment of memory elevates it as an agent able to reawaken gladness. The flowers do not simply reside on the lakeshore; they bloom anew within the recollecting mind. This process mirrors broader Romantic concerns—how recollected emotion crystallizes meaning unattainable during immediate sensation, a phenomenon also treated in critical analysis of Dickinson’s poetry. In this vision, mood fluctuates until imagination’s intervention restores delight, reinforcing the poem’s role as a vessel for hope and spiritual vitality.

Broader Romantic Themes in “Daffodils”

Wordsworth’s poem unfurls motifs central to Romantic ideology: reverence for unspoiled nature, elevation of subjective experience, and transformative value ascribed to memory. The daffodils become more than flowers in sunlight; they embody the region’s ancient hills and renewing waters, a worldview inseparable from place and moment. In this, the poem speaks to traditions explored by other Romantic poets seeking salvation, communion, or meaning in relation to wild terrain. By framing the daffodils as bearers of spiritual abundance, “Daffodils” extends the reach of nature’s tuition as well as the poetic imagination’s authority.

Solitude emerges as both a source of melancholy and revelation, yet it is the fellowship of blooms that rescues consciousness from vacancy. The collective joy of the flowers suggests kinships between individual and landscape, mood and place, echoing ongoing discourse about the relationship between art and environment. Even amidst isolation, the poet is consoled and transformed by patterns observed at the world’s edge. This interplay between self and nature, sensation and memory, presents “Daffodils” as a meditation on the means by which art translates fleeting perception into lasting delight.

The Enduring Legacy of William Wordsworth “Daffodils”

With every rediscovery, William Wordsworth “Daffodils” reaffirms art’s vital role in shaping inner landscapes. The poem’s simplicity cloaks intricate technique: dynamic structure, color-saturated imagery, gentle lyric philosophy. Readers, encountering these “golden” companions either for the first time or the hundredth, discover a work that rewards renewed attention. The poem bridges Romantic traditions of epic and lyric, binds fleeting sight to the timelessness of feeling, and stands entwined with other venerated volumes of English poetry that shaped modern sensibility. Its joy is perennial, its meaning ever-renewed by imagination’s inward eye.